from Paulo Lago

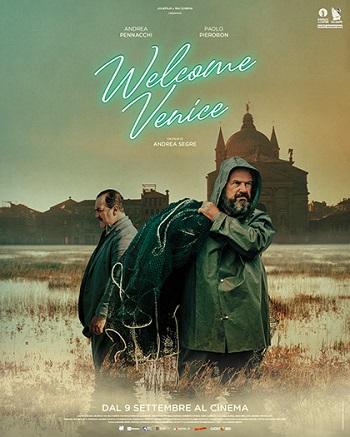

The area of the gun shown in the film as in the previous documentary film directed by the director, Molecules (2020), is deeply marked by the pandemic emergency and consequent lockdowns and emerges as its population tries to emerge from a situation of severe crisis. The film’s merit certainly lies in presenting an “alternative” vision of Venice, a city that has always been the subject of astounding overexposure in cinema and advertising. We showed not the most aesthetically attractive part of the city, the part that has become a real symbol of the leisure and tourism industry, but the most famous and least known part, Judeka Island and “Barren” (Lagoland periodically flooded with tides) where the fishermen go. In any case, on the rare moments when we see St. Mark’s Square and the more “touristy” Venice Square, the latter are framed from afar, caressed by the sunset lights, and thus placed in an idyllic look that frees them from anything. Amazing crust.

The change that the Venetian space undergoes is the same that affects the historical centers of many other cities, but Venice has the peculiarity of being built on water, where one moves only on foot or by boat. It is a change that is subject to improvement processes (a term that translates to English optimization), where the “authentic” and proletarian city space is transformed into a place of value, where the originally simple and folk houses, once renovated and redeveloped, become luxurious. Therefore, the social composition of these spaces also changes profoundly: instead of the ‘indigenous’ residents, who have been forced to migrate out of the city or to the suburbs, it takes over rich foreign residents who turn those homes into holiday homes, thus for the most part closed. general. The film tells this transformation well: Alves wants to become part of the new real estate industry that is transforming Venice while Piero tries to oppose a resistance that is also becoming a great cultural resistance. Moreover, Piero’s character is not defined in a vulgar way, he is not a naive and extroverted hunter who does not want to leave his native land. Instead, he is a very complex character, full of contradictions, struggling with a difficult past (several years in prison behind him), and is almost himself a “foreigner” in his small community. So it sounds similar to the character of Bibi, nicknamed “The Poet”, a hunter from Chioggia who befriends Chun Li, an immigrant from China, in Segre’s previous movie, I am there (2011). Like the “Poet”, who immigrated from Yugoslavia to the small community of Chioggia thirty years ago, Piero also appears, due to his irregular life, to live on the fringes of his community that he loves and feels. Precisely for this reason, the gun hunter seems to be stubbornly attached to his small areas of freedom.

The change in the area of Venice can be read through the translation key given by Franco La Cecla in local mind, which are analyzed according to an asynchronous perspective, considering the change in the living space of the city. The main assumption is that “our space” is, today, “less and less space for us”1. The urban spatial dimension, from sidewalks to streets to apartment interiors, has undergone a gradual process of gradation, creation of networks and channels, of the predetermined flows in which our lives occur. The transportation of tourists to urban spaces were city demolitions and demolitions that were carried out during the 20th century. According to La Cecla, “an irregular and intrusive space is swept away from the urban landscape, the scene of living outside and inside the door and modeling the space of cities, squares and monuments”2. The practice of stereotyping that cities have been subjected to causes – as the researcher says – a real “uprooting space”, which in recent decades has led to an increasingly frequent “voluntary or forced movement”, which is “not the movement of the nomads, but the wandering of the lost”3. Piero also wanders like a lost person: in the morning we see him sitting on a bus heading from Mestre to Venice, in a place not of his own, through which the factories. The character was uprooted from the small space of freedom he had hardly regained after his existential upheavals. It was removed from the lake, from the island of Giudecca and from its famous microcosm.

Venice has been dramatically altered by the tourism industry and its very space has become something of a “vampire”, a beauty that can be stolen and taken away. The city has turned into a kind of nowhere: the tourists we see in the movie and those who rent bed and breakfasts, after all, don’t care about living in the Venetian space. They have spent their entire stay locked up at home eating pizza and sushi, as well as foods that mark “non-places” because they can now be found anywhere in the globalized world. Tourism, as Rudolf Christine notes, speeds up and depersonalizes any dimension of travel, leading to a “wear out the world.”4.

Liberating historical centers from boutiques, which does not mean liberating them from shops and markets, but rather returning them to dense housing. And then all cities must take a path in the fresh airConsider how locking people in their homes is the principle of contagion. Living outdoors, in the middle, means going back to fairgrounds, walkways, shelters, plazas, suspension bridges, hanging gardens, playgrounds, tables and chairs, galleries, pavilions, kiosks, gardens, plant aisles, groceries, caterpillars, stalls of vendors, barbers, and theaters Streets, movie theaters, florists, musicians, tightrope walkers and flea traders. If it sounds like a vision of the past, add whatever you want, from my street number to artificial intelligence, but be careful because smart cities I am already a failure within the epidemic, indeed I am what the epidemic offers us, an alternative to life in the fresh air and in the presence of5.

Let us not forget, in fact, that the gun shown by the director is also an area of the specter of the emergency epidemic, as before Molecules. The band shoots in semi-surreal spaces and intends to provide narrative testimony to the semi-‘surreal’ state of a city crossed by thousands of problems and contradictions, also linked to pressing themes. Andrea Segre’s cinema asserts itself once again as a staunch fighter, one that has managed to tell us about the real world and its contradictions, here and now. Talk to us about contemporary spaces where human beings immersed in the same reality, more than ever, have to deal with reality, like immigrants, those who, for reasons beyond their control, are forced to leave their places and loved ones. A truth that does not seem trite, however, is always displayed through an artistic and poetic filter. However, a candidate who does not hide a thousand problems and contradictions, but, on the contrary, by a skillful game of contradictions, seems to highlight them even more.

“Infuriatingly humble alcohol fanatic. Unapologetic beer practitioner. Analyst.”